“We stand on the right side of history” was the title of the keynote speech given by Bonya Ahmed, a Bangladeshi-American freethinker, at the international Conference on Freedom of Conscience and Expression in London last month.

The price she has paid for standing on the right side of history was reflected in her troubled eyes and sliced off thumb, which testified to her own recent experience.

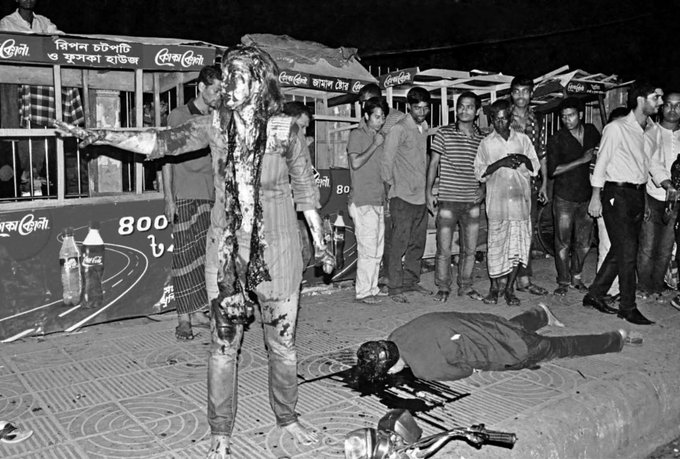

In February 2015, Ahmed and her husband, the author Avijit Roy, were attending the annual National Book Fair in Dhaka to promote his recent books when they were attacked by two machete-wielding Islamic extremists.

Roy bled to death while she survived, despite four machete wounds to her head, each six to seven inches long, and numerous others on her body.

The attack happened in a crowded street at 8pm, at Dhaka University. In an interview ahead of the London conference, Ahmed described the campus as “a fort for progressive people”. Roy was born and brought up there; his father had been a professor.

On campus progressive and leftists had waged many political battles including the fight to overthrow the military dictatorship of the Ershad government in the 1980s. Ahmed told me her husband – who had received many death threats – once said: “Who would do anything to me in my neighbourhood?”

Roy’s reputation as a prominent secularist and atheist grew after he set up in 2001 the Mukto-Mona website, the first platform of its kind for Bengali atheists, agnostics, freethinkers and secular writers. Ahmed was one of its contributors. (This is how the couple met).

If they had written in English, Roy may have have escaped the attention of the fundamentalists. But many of the people they wanted to influence were more comfortable in Bangla.

After the 2015 attack, one of Ahmed’s doctors told her that if the machete had sunk into her upper neck by another millimetre, “that would have been it”. Today she still suffers from excruciating back pain.

Of the incident, Ahmed says: “I didn’t pass out. I just don’t have the memory”. She has seen photographs, and says: “It looks like I grabbed the machete because that’s how my whole hand was cut and my thumb was sliced off. It looks like I was putting up a fight”.

For a whole hour no ambulance was called. Police officers were standing 10 yards away, staring but doing nothing. A crowd of people gathered, but only one – a photojournalist – stepped forward to help them to hospital.

They travelled in a tuk-tuk (which would have been a bumpy and unsettling ride on a full stomach, let alone with such serious injuries). Ahmed told me: “My first memory was of this guy [the photographer]…taking us on a three wheeler scooter to the hospital and I kept asking him are you going to kill us?”

Four months after the attack Ahmed was invited by the charity Humanists UK to deliver their 2015 Voltaire Lecture in which she movingly described her state of mind. “I am very scattered, my life is scattered, my thoughts are still scattered,” she said.

Two years on I ask, in the words of Canadian songwriter and poet Leonard Cohen, if the passage of time has allowed her to feel “safely gathered in”.

She responds hesitantly. “I think I am still scattered. It feels like I’m not the same person as I was before. I am going through PTSD treatment right now…. I was great for seven months, [but] every time I think it’s getting better, it just falls apart”.

She adds: “in the last three months I haven’t been able to sleep at all. I stay up night after night. When I physically fall, I mentally fall as well. I see the world in a different way now. I am constantly questioning things. How did we miss it? Did we intellectuals live in a bubble?”

Her short answer to this haunting question is “yes”.

“How did we miss it? Did we intellectuals live in a bubble?”

Since 2013, 10 secularists have been murdered in Bangladesh. How does this fit with Bangladesh’s supposed reputation as a secular country?

At independence in 1971, there was a huge secular wave says Ahmed. But: “as a whole Bangladeshi society, if you take out the intellectual class, is religious. It was not as communal or as religious or as fundamentalist before, but I think Bangladeshi people have always been religious”.

Growing religious fundamentalism is the product of a range of complicated and interconnected factors, she says. After independence, two major world events had a direct impact: the Afghan war and the rise of Saurdia Arabia as the centre of the Islamic world.

In the 1970s and 80s, millions of Bangladeshis went to work in the Middle East and many were persuaded that, as Saudi Arabia is the birthplace of Islam, their Wahhabi ideology is more authentic. Saudi Arabia also used its oil money to fund madrasas in Bangladesh.

Before independence, there may have been a few hundred of these religious schools. Today there are as many as 64,000. Ahmed says, regarding their apparent popularity, that madrasas typically provide meals and sometimes accommodation, a real boon to poor parents.During the Afghan war in the 1980s, hundreds of Bangladeshis were also recruited by the US and Saudi Arabia as fighters – and trained in ideas of the Islamic ummah (community) against nationalism and against the Soviets. Dozens of these mujahideen fighters returned to set up terrorist organisations in Bangladesh.

Ahmed notes that Bangladesh’s military dictatorship (1975-1991) also cooperated directly with Saudi Arabia and ‘rehabilitated’ war criminals, the Jammat-e-Islami, whose members had sided with the Pakistani army and engaged in rape, murder and looting during the independence struggle.

She describes Bangladesh as a case study of a “syncretic religious society” which transformed into a “jihadi terrorist community”.

Beyond criticism of religious doctrine

In her keynote speech at the London conference, Ahmed argued that it’s imperative to go beyond criticism of religious doctrine and look at political, social and cultural “enablers” who use religion to achieve their own goals.

For instance, she said it’s important to speak out against the hijab, but that she’s worried about alienating hijab-wearing women. “Why would they listen to us?” she asked.

For her, the hijab cannot be viewed simply through the lens of religion. Women factory workers, for example, may live by themselves in the cities and wear the hijab to escape harassment of men in the street.

Bangladesh is the second largest exporter of cheap clothing in the world. This is made possible by the country’s large, low paid labour force of which approximately 80% are women.

“The hijab has become an instrumental tool” for the survival of working class women, Ahmed said, so “shouldn’t we instead blame patriarchal society and the state which has failed to provide women with this minimum level of security? Shouldn’t we demand that the state provides this basic right to women?”

Despite everything that happened to her in Bangladesh, Ahmed, who lives in the US, told me that she is not afraid of returning there. She said she has lost her fear of dying.

Pointing to the chaotic world we live in, with “65 million refugees, thousands of Yazidi girls being sold in open slave markets, sex trafficking, human trafficking,” Ahmed said: “when I compare all that, billions of people living worse lives than I am, I think I shouldn’t whine about it”.

It was humbling to talk to this woman, conscious of her ‘privileged position’, even today. It is little wonder that her courage attracted one of ten awards, given out by the Council of Ex-Muslims of Britain, to celebrate their tenth anniversary at last month’s conference. Fittingly, it was in the shape of a sculpted, raised fist.

This article is part three of a series on the Conference on Free Expression and Conscience, which took place in London in July 2017.